Within a field largely astray, there are few individuals whose overall body of work has been of the caliber necessary to right the ship long off course. Among them is Dr. Gabor Maté—a man who labored for many years over the most important questions surrounding mental illness and addiction until the answers emerged at the intersection of careful clinical observation (as a former primary care physician and palliative care worker) and an extensive review of the ever-growing body of available research. Without the courage and intellectual capacity Dr. Maté exhibits, I suspect that this most significant and important body of knowledge would remain even more hidden from view, not only within mainstream news outlets, but even within higher education settings themselves, as was certainly the case during my formal educational years. But thanks to people like Dr. Maté, things are slowly changing: Today, more people are aware of the root-causes of mental illness and addictive-compulsive disorders than ever before. Yes, this group remains too small to effect many of the necessary changes at the greater, societal level, but the dismantling of outdated and unfounded beliefs surrounding the most common presentations of mental illness and addictive-compulsive disorders is certainly underway.

Since discovering his work—now more than a decade ago—I’m not sure there has been a time when I haven’t recommended at least one of his books or podcast appearances to those seeking my clinical help, with the primary recommendations depending on initial symptomology and clinical presentation. If it’s ADHD, then Scattered Minds will be it. If it’s a strained or challenging parent/child relationship, or those who are either about to become parents or work with children in some capacity, then it will be Hold on To Your Kids (which he co-authored with Dr. Gordon Neufeld, clinical psychologist, and expert within the area of developmental psychology and attachment theory). And if it’s addictive-compulsive disorders—the most common clinical presentation I encounter today—it will be, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts—the book which he is most commonly recognized for.

When looking for a viable solution to any problem, it is imperative to begin with a true and accurate understanding of the problem, including the origin and the function the problem may serve. Without this knowledge and awareness, effective solutions are left to random chance and a greater likelihood of things becoming worse in the long run, despite what may be the best of intentions or the highest of motivations. This is where Dr. Maté’s contributions are most notable. In every one of his books, Dr. Maté accomplishes this objective. With regard to addictive-compulsive disorders specifically—the primary focus of this piece—with his keen observation and deep knowledge of the literature, Dr. Maté has been able to effectively dismantle many longstanding yet wildly inaccurate and scientifically unsupported beliefs, beginning with the notion that addictions are heritable diseases and/or the product of some genetic malfunction—two ideas that are demonstrably false.

Instead, Dr. Maté came to realize that addictive-compulsive behaviors are never the root problem, but rather an attempt to solve a deeper problem, often unrecognized, and this is the function they serve (perhaps even a lifesaving one at earlier periods in life, which I will describe in more detail later). Yes, while it may be difficult to believe, even with the seriously detrimental and sometimes deadly outcomes addictive-compulsive behaviors can lead to, with a proper search effort, a positively motivated intention and short-term benefit will be found. Because this has not been standard practice, this may help explain why there has been such little progress with regard to mental health and addiction treatment in general: In most settings, the symptom is treated, while the root problem is left unrecognized and untreated.

To illustrate, consider a physical illness like bronchitis, which often produces the symptom of a cough. While most doctors would not make this mistake today, it is easy to see how mistaking the symptom for the problem and/or only treating that symptom would, in all likelihood, only produce short-term benefits. Here, if the cough was treated with a cough suppressant, while the bronchitis itself was unidentified or ignored, there may be some welcomed, short-term relief that is made available, but as a standalone treatment, it would almost certainly be ineffective in the end. With addictive-compulsive behaviors also being a symptom, Dr. Maté eventually discovered that in all cases, addictive-compulsive behaviors—regardless of the specific compulsion—share a similar objective: The attempt to sooth or distract from unresolved psychic pain (primarily that which stems from unmet psychological needs during one’s developmental years, which leaves significant emotional pain in the wake in all cases, and permanent injury in some as well). Yes, this means that in the world of the psyche, time does not, in fact, heal all wounds, as we have been mistakenly led to believe.

With this important discovery, Dr. Maté encourages the afflicted and/or those tasked with helping to begin the process by asking the question, “Not why the addiction, but why the pain?” With this simple yet profound change in focus and intention, even though there will be considerable work ahead, genuine healing and recovery are made possible. However, this brings us to the one area where I find Dr. Maté’s understanding to be limited or incomplete (and one reason for me writing about this topic here). I believe Dr. Maté credits this type of intellectual exploration, discovery, and understanding with more “healing” potential than is deserved. While it is an important and necessary first step; in my experience, long-term success requires a deeper level of healing that is far more difficult to achieve than I hear being described by many of the prominent voices in the field, including Dr. Maté. In my experience, intellectual understanding alone is insufficient and must include and be informed by the physical-emotional realities of the primary wounding experience(s), which can only come from a direct re-encounter with the holdings within the physical-emotional body, as were true to the original experience(s), but which were unconsciously buried or split off from if we lacked the capacity and/or the supportive resources necessary to tolerate such intensity as a dependent-aged child.

Note: when referring to physical-emotional processing, I am referring to the body’s innate physical responses to specific emotional states if they weren’t being interfered with by ourselves or someone else. To illustrate briefly, the emotional state of sadness produces the physical response of crying; intense fear may produce a trembling or shaking response; shame or disgust routinely brings nausea and the urge to vomit. These are a few examples of our body’s physical responses to “negative” emotional capacities, and it is our willingness and ability to allow the body access to these responses that begins to metabolize those unwanted emotional states and the symptoms they produce, while denying such experiences maintains and feeds them.

In every encounter where I have witnessed or experienced this type of physical-emotional processing work first-hand myself, it has been very difficult for those going through it to fully surrender to the needs and requests of the body. Without exception, everyone resists full expression at least for a period of time, while most never give up their resistance completely. And because of this difficulty, most clients and clinicians collude in pretending that this step can be bypassed, suggesting that sufficient healing can be achieved through less intense means.

But, if you lose your cars keys in a dark, scary, back alley somewhere, you’ll have to go back into that alley if you want your keys back. They will not be found anywhere other than where they were lost. Similarly, if you had to split off from parts of yourself because your environmental circumstances were such that it was too painful or too unsafe to hold on to those parts when you were a small child, those parts—often the most authentic, vulnerable parts—will be found in the physical-emotional, body-based memory of what prompted the splitting to occur, and those deeply unpleasant feelings will be your truth-seeking chaperone.

A common phrase I hear from the addicted population is this: “I don’t know who I am,” which is often accompanied by a sense and strategy of “trying to fill a hole” (via the addictive-compulsive behavior). And these are reliable indicators that a splitting/forgetting occurred at some previous point in time. Here, healing and a sense of wholeness requires a successful “recovery” effort. Sadly, this term has come to mean “sobriety” in most settings, and I recommend not confusing these terms in this way. Instead, I am suggesting if sobriety or long-term change is the goal, genuine recovery should be the objective.

Where the afflicted find the strength and resources necessary to locate and work through this unresolved physical-emotional material, I have observed the addictive compulsive-behaviors which were once tasked with keeping this material from surfacing diminish significantly or abate altogether. This occurs because once the “why” changes, the behavioral response strategies change in kind. This means that when the underlying psychological pain that birthed the compulsion is reduced or resolved, the strength of the compulsion which had been needed to sooth or distract from that pain, is also diminished or resolved in similar proportion. Just as most people would not continue to use a cough suppressant after a cough-producing illness like bronchitis is resolved, people also do not continue to engage in excessive emotional soothing or avoidance behaviors when the psychic pain that underwrote those behaviors in the first place is diminished or resolved altogether.

And it is very important to highlight that attempts to override the natural architecture of the human design on either a physical or psychological level, including engaging in the suppression practices of the physical-emotional experiences we deem “negative” (something virtually all modern people have been socialized to engage in from their earliest years of life), not only makes us sick, but keeps us sick as well (as long as we maintain suppression based practices). Simply stated: Health cannot be achieved through a deliberate war waged against the physical-emotional body any more than kinetic wars lead to world peace.

It is also the case that due to the degree of difficulty, most people will need some help/support with this type of work, especially in the beginning when that terrain can be very confusing, disorienting, and frightening. But for those who find the courage and the help to engage such highly vulnerable and deeply challenging material, the liberation that is discovered helps to eliminate the need for the historical remedies consisting of life-long, disease-management protocols and psychotropic medications.

And, whenever troubling compulsions remain, these ongoing symptoms may serve as signposts for the yet-to-be identified or fully resolved physical-emotional work that remains (much of this work also takes longer than we would like as well). Often, in the beginning stages of treatment, people will disagree that this could be true for them, and they will genuinely struggle locating any noticeable psychic pain. This might be you reading this now. And this speaks to just how effective addictive-compulsive behaviors can be: They make it so you don’t even notice the impressive work they are tirelessly doing to keep you unawares (either from content, the related physical-emotional material, or both).

Substitute Addictions:

Unfortunately, in many cases when a particular addictive-compulsive behavior becomes too problematic for someone, substitute addictions will often be explored and implemented next. For example, as you might expect, I regularly encounter those experiencing significant problems stemming from substance-abuse disorders. Often, instead of working towards identifying and resolving the wounds that fuel these behaviors, the afflicted will swap addictive-compulsive behaviors instead. The list of potential swaps is endless, but the most common ones will be those on the “positive” end of the spectrum; that is, those with more social support and approval, which might include things like fitness or dietary changes, or work/career-based changes, making them potentially even more difficult to let go of down the road. And while it can certainly be argued that some swaps are better or healthier than the original addiction, any addictive-compulsive behavior can become extremely destructive, not just to self, but to others as well.

Moreover, since substitute addictions do not resolve the core wound(s) that birthed the compulsive drive, no amount of whatever is achieved by way of the substitute will satiate beyond the immediate and the temporary. For example, as I will describe in the next section: The workaholic will never earn enough money or accomplish enough goals to achieve the state of peace they are ultimately looking for. As a result, exhaustion, not a sense of increased peace and security, is almost guaranteed to be an ongoing companion for those who choose substitutes over resolution. Ultimately, addictions are a form of avoidance, an act of running, fleeing, or trying to escape the realities of the psychic wounds one carries, and constant running leads to exhaustion, especially when you cannot tolerate what comes if you stop, and you have to “just keep going” as a result. This—any addict will tell you—is a terrifying stage: As the end of the road draws near, the sense that, “I can’t keep running, but I won’t survive if I stop!”

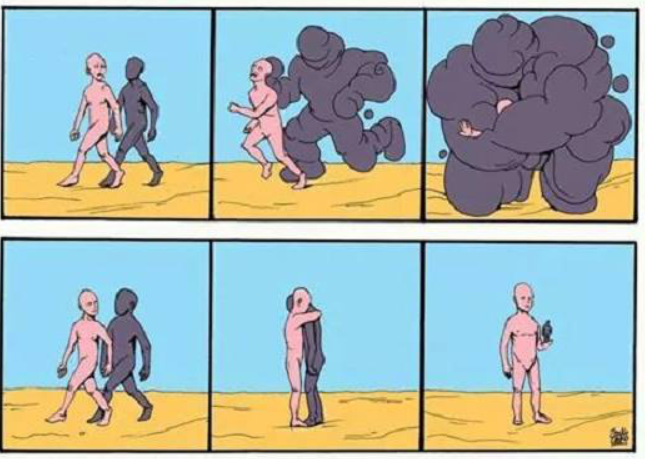

It is said that a picture is worth a thousand words. I came across the illustration above years ago, which captures what I’m trying to describe. Whoever created it certainly understood the therapeutic process through completion. In this six-panel illustration, addictive-compulsive strategies keep people in the second frame. This is preferred because no one wants to experience what takes place in the third frame, and this is exactly what happens if an addiction is given up without deploying another distraction to replace it. But for those who stop one without substituting, if they can learn to fully surrender to what comes in frame three (again, this usually requires help), frames four – six naturally unfold as depicted.

A Case History:

While more detail will be offered in the upcoming book, I decided to briefly share a few details from my own personal encounters with addictive-compulsive disorders here, which I hope will better demonstrate the dynamics I’ve described above in a more complete and accessible way.

For me, the first symptoms of unresolved psychic injury emerged as extreme fatigue and a lack of motivation (known well by those who also suffer these symptoms as elements of depression). At that time—then late teens to early 20’s—I adamantly rejected the notion that I could be a depressed person. Note: Often, a reliable sign you may have a particular problem is when there is a fierce denial surrounding such possibilities, and this was certainly the case for me at the time.

Unfortunately, while I had known that many of my early life experiences were certainly bad and should not have happened, especially the way my father had treated me when I was growing up, it would be many years before I properly understood the breadth and scope, and overall significance of those early-life injuries, including the role those experiences were continuing to play out years later, long after I had finally escaped the abusive environment I grew up in. This, I have found, is another common mistake: Believing that once the abuse ends, and there is some safety or distance established, the impact of the abuse ends there as well, and that it will be blissful days ahead once we get there. This, I’m terribly sorry to report, is patently, untrue.

Eventually, as they are known to do, these symptoms increased to a point where they could no longer be ignored. Many of the things I enjoyed most in life were beginning to be compromised. Pleasure from hobbies and passions, such as playing and listening to music, diminished substantially. Once that happened, like most people, I began to seek answers, scanning my immediate environment for possible culprits (of course only locating those potentials I could tolerate the possibility of being true at the time, significantly diminishing the odds of success). It did not take long to settle on two likely suspects: physical and financial health. I wasn’t in terrible physical shape, but I knew my diet could be cleaned up, and I had come to believe a healthy diet would make the difference in my energy levels. And, I was drowning in debt and had difficulty making ends meet, which was causing real and persistent stress, so these became my target areas for improvement.

I began experimenting with dietary and fitness-related solutions first (likely because this was the easiest of the two)—something I enjoyed learning about and continued to study with some passion for much of my life. Thankfully, what I learned and some of those changes I made led to some improvements that have been maintained to this day. Unfortunately, however, despite a few initial attempts to convince myself otherwise, none of those efforts made much impact on the depressive symptoms I was most trying to alleviate. Later, after years of focus on improving my physical health failed to provide the relief I sought, I now fully believed improving my financial health was mandatory—something which wasn’t entirely untrue.

Prior to and shortly after graduating college, most of the jobs I had not only didn’t pay well, but they were also not well-aligned with my talents or interests, and I correctly figured this was also something that needed to change. In college, I chose to major in what I believed to be a higher income-generating field of study (rather than what I was passionate about): accounting. I was also attracted to this field initially because it kept living options open, as accounting was a needed service in every US state, by every industry. The bad part: I wasn’t very good at it, and I did not like it at all! Thankfully, as part of the degree program, I had to take other business courses, including a Managerial Finance course, which I actually did really well in and enjoyed a lot. But with little experience and a degree specifically in accounting, entry-level accounting jobs were mostly what I could get, and the highest paying work I could find was mandatory.

And then, one day, with a great deal of fortune, or misfortune (probably both), shortly after leaving what was viewed by many as a foot-in-the-door, high-level corporate accounting job that I was especially miserable in, I met a man randomly on a mountain biking trail who was having trouble with his bike. We were at some considerable distance from the parking lot, so I decided to stop and ask if he needed help (not that there was any help I could have really offered). He ended up finding a temporary solution to a small mechanical problem with his derailer. For some reason unbeknownst to me at the time, I decided to ride back to the parking lot with him instead of finishing my ride.

On the way, the normal introductory chitchat ensued. There I learned, among other things, that he was new to the area (Colorado), having just moved from Texas for a job opportunity. As I listened and asked questions about this new job of his, I found myself becoming very excited and intrigued about what he was describing. From what I was hearing, this sounded like my “dream job,” especially when he shared the earning potential, which would be enough to eventually get me out of the suffocating debt I was in. The only problem I could identify from what I was hearing was that it was a 100% commissioned sales position as a residential Loan Officer. But this job would employ the financial skills I possessed and enjoyed using, while allowing me the opportunity to set my own schedule and that was enough positive for me. By the time we both arrived back at our cars, with my interest clearly noticeable, he mentioned that he thought the owners were looking to hire more people. I found the courage to ask if he’d be willing to connect me; he said he would, and we exchanged numbers.

Soon thereafter, I ended up getting a call to interview with one of the owners. This was many years before the Wolf of Wallstreet was released, and this was the first sales position I ever applied for, so I did not expect him to slide his pen across the table and ask me to sell it to him. By either magnificent luck or divine intervention, in a fairly panicked state (I had not seen this coming at all, but I knew everything depended on what I would say next), I somehow found the words and the questions I needed to close the deal: I sold my first pen, and I was offered the job!

It was sink or swim time, with homelessness now on the near horizon. With no one in my life believing it was the right choice, I decided to go all in: This was my one and only chance, and I knew it. The first couple of months were wrought with heavy stress and worry, but as predicted, I did really enjoy the work. Back then, we had some very advantageous loan/financing options that were especially beneficial to borrowers, and I enjoyed showing people different ways they could save on upfront fees and future interest. I loved using what knowledge and skill I had acquired to help people with the largest and most important financial decision most would ever make. I prided myself on my customer service and I went above and beyond for people, and as is true today, honesty and integrity were my guiding principles (I would never sell something I did not believe in, could not be completely honest about, or would not use myself if in their shoes).

And, to my most pleasant surprise, this led to those depressive symptoms finally lifting for the first time in years; hallelujah! In relatively short order, I was no longer fearing homelessness or hunger, and my general mood and energy levels vastly improved. After years of desperate searching for ways to feel better and to be more motivated, I couldn’t be happier with where I was now. At that time in my life, with my limited knowledge and significant aversion to being a depressed person, I only knew depression as a motivation killer, and I was ultra-motivated now, which was enough to convince me that I was right: I was never a depressed person after all; I only lacked a good paying job that I enjoyed which afforded me lots of freedom and control over my schedule. Things continued to go very well, and after the first few months, I significantly decreased my marketing efforts. My reputation and customer service quickly led to a steady stream of referrals, and I was often the top producer in the organization I worked for. And all of this led to genuine praise and appreciation from customers and colleagues alike, including both of the owners of the company I worked for.

Unfortunately, however, what initially appeared as the promising solution was actually a recipe for future disaster, but that would not fully unfold for many years. First, I eventually got a surprise visit from a symptom I had not seen coming. Following the last closing of one of those earlier months, knowing that with the next check coming I would be able to pay off the last of the remaining credit card debt I had, I was blindsided by an episode of heavy sobbing that seemed to come out of nowhere, while driving home late one evening. It was shocking, and I could not make sense of what was happening to me.

As most people do, I quickly scanned my immediate circumstances, believing that the source was surely in close proximity, but I found nothing that could explain this reaction. I just had a record setting month (for myself and the company), and I was feeling more financially secure than at any point in my life prior. I was dumbfounded. The only explanation I could find—which was ultimately very far off from the truth, and almost embarrassing to admit to now—was that I hadn’t reached all my income goals yet. Yes, I was getting out of debt, but owning my own home was the real goal and I wasn’t there yet, nor did I have any savings to speak of either. Out of debt was great, but that wasn’t the ultimate goal, and apartment life was taking its toll, so I figured “more” is what I needed, and I took this as a sign to keep grinding; everything was just fine!

What I originally thought was resolution was instead only the temporary relief afforded by an effective addictive-compulsive defense strategy. Making things more complicated, my primary addiction was one of the culturally endorsed, “positive” ones (which are common substitutes for others), so it was even more difficult to spot and eventually treat. Made trickier still, while my workaholism would eventually cause great harms, as most addictions do, it was also the case that it saved my life in many ways before it became the destructive force it ultimately did, as alluded to earlier.

The list of traumatic experiences I endured in childhood is substantial, and I was never fully in denial (the most common, front-line, psychological defense), but like most people, I also had limited awareness with regard to just how bad it was and/or the extent of the damage those experiences actually caused. For example, I did have some limited, intellectual awareness that being told on an almost daily basis throughout my childhood that I was a, “lazy, worthless, no-good, piece of shit,” and that I would, “never have anything, be anything, or ever find anyone who would want to be with me,” was very hurtful and not something I should have ever had to hear, especially from my father. But the depth of that hurt and the full impact it had was still largely suppressed and thus unknown to me.

Today, with more experience and wisdom, I can easily see what I could not see back then. Remember when I said every addiction has a function? Well, in my case, the “ultra-motivation” I had developed was my addictive-compulsive attempt to silence those criticisms. And the praise, appreciation, and related financial success made me feel—temporarily at least—as if those words from my father were untrue and did not matter, setting the stage for what would eventually become a terribly destructive workaholism that lasted for more than a decade, and long after my need for the helpful aspects had passed.

Yes, while there were other factors at play, I acknowledge that without this workaholic drive, I would not have escaped the abusive environment I grew up in as soon as a I did, nor would I have been able to work full-time while attending school full-time, which was necessary in preparing me for the lending job and the success I was able to have there. And without the lending job, I would not have been able to support myself while attending and finishing a graduate program years later. And in the early days of being a therapist, I certainly would not have learned what I did without sitting with so many people, while simultaneously engaging in the outside study necessary to actually be effective in that role (sadly, graduate school did not prepare me for most of what would be encountered in the therapy room). But it was also the case that this relentless pursuit of “success” (measured not only through income, but later through degrees, licenses, credentials, and goals in general) ended up being something I did beyond when it could truly be defended as a legitimate necessity (finishing my doctoral program being one clear example), and certainly beyond what my body could tolerate.

For more than a decade I averaged between two and four hours of sleep most nights, and it wasn’t until I had found myself in two car accidents, both within a very short period of time toward the end of my doctoral program. My body was finally giving out from years of sleep deprivation, and these events forced me to be more honest with myself and consider the potential that I had a bigger problem than I had been willing to see or admit to prior. Among the more difficult lessons I’ve learned in life is this: People do not change until not changing is scarier (or more painful); meaning, we will not face the discomfort inherent in the change process until the discomfort surrounding the way things are becomes greater. Here, we must find a sufficient “why” (motivation) in order to walk that very scary, unknown path.

With the first accident, in my highly sleep-deprived state, I was approaching a redlight at a busy intersection, which I did not register until it was too late. With cars now crossing the intersection, I came to just prior and slammed my brakes. Unfortunately, this did not prevent me from sliding into the intersection and hitting someone, but it did allow for some slowing and decrease in impact. After it happened, I knew I could have killed a man, husband, and father, if I had hit his door instead of the rear driver’s-side door I struck instead due to the braking I was able to apply. In that moment, at least one thing became clear: I could no longer deny that I had to make changes, and I also knew leaving the doctoral program was mandatory.

I tried as hard as I could to make that happen and I failed. A couple weeks later, I was in another accident, for similar reasons. While this one was minor in comparison, I knew this would be my final warning. Thankfully, having had one positive therapeutic experience previously (another story for another time), I was at least more open to seeking help, and it was now clear: I would not be getting out of this on my own, and there was no more time to stall.

Thankfully, I found some help and I took it: This isn’t always a given; in fact, more people reject this type of help than accept it when it’s available. By the second session, the counselor suggested this problem could be related to my relationship with my father. My initial response: “No, it can’t be that because I already dealt with that.” Thankfully, I remained flexible enough and considered her assessment, and the possibility I might be wrong or missing something. In the end, she was right, and I came to realize I had only dealt with the first layer of that wounding and there was more—a lot more! And after I began working on those wounds on a deeper level (not the deepest, as I would come to learn years later, but deep enough this round), I was able to resign from the program, and I began setting boundaries with my work schedule, two things I was unable to do prior.

But giving up the workaholic lifestyle meant creating space for the voices and the painful reminders surrounding what I had actually been through as a small child. The truth was most bitter, and very difficult to swallow: There would never be an amount of external praise, admiration, or achievement that could or would make up for the reality that I would never know the experience of being loved, valued, understood, protected or supported by a father, and I would have to find some way of living out the rest of my days no longer in denial of this truth. Not easy, I promise!

Eventually, I found the only viable way to live such truths: learning how to grieve. I still remain surprised that a human being can survive the full intensity of profound physical-emotional experiences like this, but even small encounters help one understand the benefits of addictive-compulsive behaviors and their prevalence in modern times.

In practice, everyone who’s walked into my office over the last 20+ years automatically attempts to suppress their tears, which usually surface as soon as they begin to share what brought them there, addicts especially. Here, everyone is hoping for the same thing: A way to not have to go there—into that pain, the fear, the confusion, the despair, the anger, and the vulnerability of it all. They scramble to find a way to bypass having to. The search for solutions come quickly in hopes that the intellect might deliver some way of remaining “in control” of what happens next. Grief, on the other hand, offers no such illusions of control, and the very real possibly of being hurt further by sharing it with someone who doesn’t understand, doesn’t care, or who gets too scared of what may come up to remain a faithful witness and a grounding presence in the proceeding. These challenges and a desire for easier ways are why such little progress has been realized in the world at scale.

Summary:

So now, with this personal example in mind: Returning to Mate’s question “Not why the addiction, but why the pain,” being unwanted and unloved by my father brought an intensity of psychic pain that was in direct proportion to the intensity of the addictive-compulsive drive I developed, and the workaholism was the temporary, but never fully satisfying, solution that helped me successfully avoid the grief work that rightly belonged for years. The fantasy that had given me a false hope that I could somehow make the past untrue through future results could never work long-term. It was a scary thing to lose, as the pain was significant. Now then, it may not be as surprising that when I found a culturally endorsed addiction that offered something close to what I always needed but never received (kindness, appreciation, and admiration for my talents and skills), I was hooked, in the truest sense of the word. And like all addicts, I was unconsciously terrified of stopping and letting all that hurt come back to the surface.

Wanting to avoid truths like this is understandable, but the destruction created in those pursuits is more costly in the end. It is also the case, despite my deep desire for it to be otherwise, I could never have put all this together or found a way out on my own, and part of that was due to the innate desire we all have to avoid such extreme pain, especially that which is familial in origin, making ongoing self-delusion highly likely without getting help. As mentioned, the other option is substituting an addictive-compulsive strategy, and I have recently worked with people who are substituting substance abuse addictions for the more socially acceptable ones like I had, and so far, all signs point to a similar future demise. In fact, someone who made this swap recently said, “I can see how this (hiking/fitness/travel obsessions, in this case) could become a problem,” but decided it was still better than facing the truth and the related pain he carried. Again, such choices are understandable, but not advised, as the suppressed and unresolved emotional material behaves like interest on an unpaid loan, continually accumulating at an accelerating rate over time.

Today, most people faced circumstances early in life where they had no choice but to deny or dissociate from what was really happening. These are never conscious decisions; it is an innate safety feature of the human organism that is deployed when we do not have a fight or flight option, as is true for all dependent-aged children in physically or psychologically dangerous settings. Because a child cannot set boundaries, enforce boundaries, or physically defend themselves, denial and dissociation are the only safeguards available. As I have demonstrated in other writings, and as is demonstrated in two of Maté’s books I have not mentioned yet, When the Body Says No: Exploring the Stress-Disease Connection, and The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture, the data are quite clear: physical-emotional suppression is toxic to hold in the body long-term. And I have also found that as soon the psyche recognizes that the “coast is clear,” the body begins sending signals for the necessary release and the purging of emotional material still held in the cells of the body.

Often (as demonstrated in my story), this can really throw people off the scent. “Everything is great in my life; I shouldn’t feel this bad; there’s no reason,” I’ll hear people say. My response: “That might be exactly why you’re feeling so bad… because you now have enough resources available to finally deal with this old, unresolved material.” I also saw this phenomenon working with combat veterans. Most returned home and did great for several months, and then, overwhelming symptoms of depression and/or anxiety would suddenly appear. From what I’ve learned about combat, it isn’t constant action. There are frequent periods between missions, for example, where explosions and gunfire are not occurring. Knowing the delaying capacity of the psyche until it’s finally safe (the exception being when the traumas are too great in amount or strength, and the container fills to its maximum first), my contention is that those symptoms knew not to surface until the sounds of explosions had stopped for a long enough period of time to suggest they were no longer in the physical danger of a combat zone.

The psyche knows that if the body does not survive, one’s psychic health matters little, so the body always gets priority, but again, if the body either becomes full or detects sufficient safety now exists, then it tries to purge/process that physical-emotional material, regardless of how bad the purging feels (no different than if you ate something bad and got food poisoning). In this way, mental health conditions and addictive-compulsive disorders are signs that this type of processing and reconciling is needed as a means of restoring health to the mind and body, to the degree possible, depending on the significance of the prior wounding.

The human design is truly a marvelous creation: It comes equipped with everything it needs to thrive, but those features need to be understood and respected, as they cannot be overridden long-term without significant detrimental consequence. Most of our troubles today come from training young children to override the natural processes of the body, while adults maintain the same disposition themselves. As the increasing rates of mental illness and addiction attest, the body will never submit to our attempts to make it otherwise; the symptoms produced in those efforts will only become louder instead.

It is with the great lament that this marvelous creation remains so badly mistreated and so deeply misunderstood in modern times. If we ever cease trying to change the organism in these destructive, dishonoring ways, and learn to finally adhere to and respect our fundamental nature instead, we can recover. If we continually choose denial and the avoidance of re-learning how to process our wounds instead, we can expect more and more destruction and devastation at the individual and societal levels, including a continual increase in addictive-compulsive disorders needed to help in the avoidance effort. I hope one day we will choose the former, as it does not look to me like we can afford much more denial and avoidance. I’ve had the great privilege of seeing what that choice leads to many times now over the past couple of decades, and it is clear to me that this is a mandatory skill for everyone to work toward developing if we care about the wellbeing of ourselves, and the species as a whole.